Here I dive into the nitty-gritty of my new improved strategy. I spend an entire chapter on one vital topic: aggression – both using it, and facing it. If you wish, you can start reading at Chapter 1, or download the entire e-book as a PDF.

Being Aggressive

Because I am a naturally risk-averse person, one of the greatest lessons I’ve learned in the last couple of years is that aggression is often the lower risk path in poker.

Here’s a classic example: We’re playing $2/$5 no-limit hold’em, there’s a limp, and then the cutoff makes it $20. I’m on the button with pocket nines. The old Lee calls that raise. I have a pocket pair, I can flop a set, and good things can happen. If I don’t flop a set, meh, I’ll wait for the next good hand.

The new improved me 3-bets that spot virtually every time. I could wax poetic about the advantages of 3-betting rather than flatting the raise, but I actually wrote an article about why 3-betting is so great.

I find it easy to make the 3-bet because of the way it makes me feel. Specifically, I don’t find myself in a three- or four-way pot on the flop, thinking that I have to flop a set or give up. Instead, the action usually folds back to the original raiser, and it’s me against them, with me in position. Sometimes, the initial raiser folds too, and that’s a great outcome.

This 3-bet, and many just like it, have simplified my poker life, and actually made things easier, not scarier. This is emotional gold to somebody who doesn’t like uncertain and confusing situations.

I am playing a nearly 100% 3-bet-or-fold policy behind open-raises.

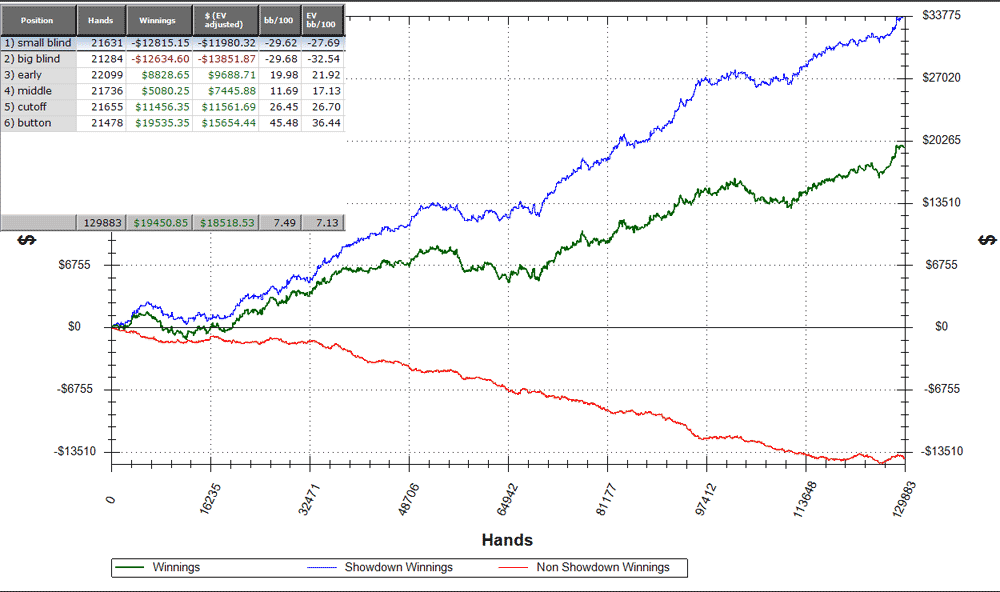

I am also playing a nearly 100% 3-bet-or-fold policy in the small blind. It forces me to be highly selective about what I play there – after all, it’s the worst position at the table. If I don’t feel good enough about a hand to 3-bet it in the small blind, I don’t play it at all. It’s live poker, so I don’t have nice, clean PokerTracker results to prove how effective this is, but I find myself in a lot fewer awkward out-of-position spots. I am persuaded that this is improving my bottom line.

It is dangerous to say that one can “see” the effect of a certain style of play – poker is full of variance and unintended consequences. But I’m prepared to say that I can see the improvement that increased aggression has brought to my game.

Just a couple of nights ago, I found myself on the immediate left of a competent, aggressive player. I had 3-bet him three times during the session. On this hand, he open-raised, and I had a close decision between 3-bet or fold. It took me a second to decide, and then I folded. It folded all the way around, and as he scooped in the chips, he said to me, “If you had 3-bet me again, I was going to call the floor and complain about bullying and harassment.”

I gave him a polite, silent smile, but inside, I was dancing a jig.

At every juncture of a hand, I am forcing myself to consider an aggressive, rather than passive, action. If aggression doesn’t seem warranted, I ask myself if I should fold. Only when aggression and quitting the hand have been rejected do I call.

“The one who bets the most wins. We just use the cards to break ties.”

Sammy Farha

Folding to Others’ Aggression

There is a flip side to the aggression coin: when a passive player shows significant aggression, I am quick to fold.

Recall that I play all my poker live, where most of the losing players share two important characteristics:

- They are overly loose and passive – they call when they should fold, and call when they should raise.

- They are showdown driven – they usually want to get to the showdown for the least amount of money possible.

Consider this common player: one who checks when they should bet, and calls when they should raise. When such a player chooses the more aggressive choice, they have a far stronger hand than the solver would need to make the same choice.

Suppose I’m playing $2/$5 NLHE. I open to $20 UTG+1 with A❤️K♣️, and only the small blind, who is unknown to me, calls. We both started with $500. With $45 in the pot, the flop is A♦– 4♠️- 8♣️.

My opponent checks, I bet $20, and they call. With $85 in the pot, the turn is the T♣️. My opponent checks, I bet $60. But now they check/raise to $140.

I fold.

In low-stakes games, raises on later streets – particularly check/raises – are almost always better than one pair. I don’t know if my opponent flopped a setor made two pair. But I don’t care – both of those hands crush mine.

One way to exploit overly passive players is to not pay them off on the rare occasions that they turn aggressive.

“What if they’re bluffing? What if they have A♣️5♣️ and turned a flush draw with their top pair, and are now semi-bluffing?”

Then good for them – they win the pot.

This is where poker math comes into play. Few players bluff at the optimal frequency. We all tend to under-bluff relative to theoretical bluffing frequencies. I wrote an article about the GTO response to under-bluffing: it is to fold all of your bluff-catchers. When a passive opponent check/raises on the turn, my top-pair-top-kicker is a bluff-catcher. That is, I don’t believe my opponent is raising a worse hand (e.g. AQ) for value – if I call, it is only to beat a bluff.

So I fold.

Am I exploitable when I do this? Absolutely. But in the immortal words of Tommy Angelo, “Just because I’m exploitable doesn’t mean I’m being exploited.” In fact, by refusing to pay them off when they get aggressive, I am exploiting them for their overly-passive play.

The moment I exploit my opponents’ mistakes, I become exploitable myself. But it’s totally worth it.

As an aside, I am careful not to fall into the trap of, “I can name a bluff they might have.” I see this in poker discussions all the time – the protagonist realizes that their opponent could have a particular bluff, so they call. But that’s not the point. The point is whether they have enough bluffs relative to their value hands that I have a profitable call.

With rare exceptions, they don’t have enough bluffs, so I fold. People say, “If I fold here, I will be exploitable.” They seem to forget that if they call any time their opponent could be bluffing, they’re also exploitable.

Listening to What My Opponents’ Bets Are Saying

Just today, I heard a poker vlogger say, “He can’t have aces here because he would have 3-bet those preflop.” This, not ten minutes after the same opponent had flatted KK behind the hero’s open raise. Poker players, particularly unstudied ones, do weird and seemingly random things.

I am careful not to assume that my opponents will do what I would do. And I don’t assume that they play theoretically correctly.

Some Broad Strokes Apply

Even though I don’t ascribe my own behavior to my opponents, there are reliable concepts I can use to narrow my opponents’ ranges. For instance, the more hands they play preflop, the weaker their post-flop range will be. This is true no matter what algorithm (or dart-throwing process) they have for seeing a flop.

If I bet, and my opponent calls, their range just became stronger, because they threw away the hands they consider hopeless. Now their range is stronger than it was before I bet.

These are not the sort of reads that narrow my opponent’s range to a certain kind of hand. But they do allow me to bucket the opponent’s hands into strength categories, which is exactly the kind of insight I need to guide my play on later streets.

Listening To Their Bets

I keep coming back to this because it’s so important: Weak players are loose, passive, and showdown-driven. They are overly focused on answering the question, “Who has the best hand?”

When such players want to pile extra chips into the pot, my first assumption is that they have a strong hand that they like very much.

When I get conflicting signals between inferring a rational series of decisions by my opponent and believing their bets, then I believe their bets.

Suppose I’m playing $2/5 NLHE. Three people limp for $5. I make it $30 in the cutoff with A♦K♠️, and two of the limpers call. We all started with $500.

With $90 in the pot, the flop is K❤️-7♣️-4❤️. Everybody checks to me, and I bet $50.[1] Only the first limper calls. Now we’re heads-up with $190 in the pot, and the turn is the T♠️. My opponent checks, I bet $140, and they call. We’ve got a big pot – $470. The river is an inconsequential 2♦, but suddenly my opponent lead-jams for $280.

First, I stop and consider the situation. I need to be good 28% of the time to have a profitable call. The flush draw missed. The most obvious straight draw (65) missed. There are no obvious two-pair combinations. From a hand-reading perspective, no better hand makes sense. But then again, no worse hand makes sense, either. My opponent’s story just doesn’t make sense, period.

I often hear people say, “When the opponent’s story doesn’t make sense, I tend to call.” I don’t expect my opponents to always tell sensible stories. So when their stories don’t make sense, I start looking for other information to guide my decision. In this case, an opponent who is passive and showdown-driven has suddenly put the rest of their chips into the middle.

There will be some times when this is a last-minute panic bluff. But far more often, I’m facing a hand that beats my one pair. Whether it’s a flopped set of 7’s, KT, or T♣️-2♣️ – I don’t know. I just know that they have a better hand than mine way more than 28% of the time, so I fold.

When my opponent’s story makes no sense, I believe their bets. There is no “sensible story” requirement to have the best hand.

[1] Theoretically, I should be betting much smaller multi-way (e.g. B20 instead of B55). But because I expect my opponents to check/raise much less than they should, I can get away with a bigger size. With very likely the best hand, I benefit from that larger size.